Part 4 /4

Yemen:

a man-made crisis

A photo reportage from deep inside a country devastated by an unprecedented humanitarian crisis.

Images and text by Lorenzo Tugnoli

Lorenzo Tugnoli is an Italian photographer based in Beirut from the photo agency Constrato. He won the World Press Photo 2019 reportage award for his work on Yemen. He is one of the last photographers to visit the country between November and December 2018 in Houthi-controlled area. Disclose publishes its report in exclusivity for France

Rageed is a small bundle in his grandfathers’ arms. He bears the unmistakable signs of malnutrition. A swollen abdomen and sagging skin around his tiny arms.

His father is not at home; from the remote village of Al Abar he walked through the mountain to beg in the market of the nearby town to try and scrape some money to feed his children.

An old man holds his grandson, Rageed Sagheer, four months old. The baby is severely malnourished and needs to be taken to the clinic in Aslam but the family cannot afford the transportation.

The family lives in a mud house on top of a small hill. Inside the hut, I squatted and took some images of Rageed’s grandmother as she fed him the last batch of powdered milk; after this there will be no food left for him.

Rageed Sagheer is fed what little milk is left by his grandmother.

Four-month-old Rageed Sagheer is not the only child in this condition; in every village and town of Hajjah province there are children like him.

A woman sits outside her house in the village of Al-Jarb. It is extremely challenging to reach health care facilities for families that live in remote villages like this one. Since the start of the war fuel prices soared and poverty increased.

The markets are full but prices more than doubled in the last few years and the poor farmers in the region, who survived with few dollars a week, plunged into famine.

Food stands in Souk al Meleh, in the old city of Sanaa, the capital. Here as well as in the towns across north Yemen there is no lack of food. But war and inflation have pushed the cost of food so high that many people cannot afford to buy it any more.

Over two extensive reporting trips last year I encountered starving children in hospitals and refugee camps all across the country. This humanitarian crisis was not created by a natural disaster; it is a man-made famine that has been used by both warring parties as a tool of war.

The Yemeni government and the Houthi rebels have been at war for four years, now more than half of the population lives in conditions of near starvation.

A checkpoint in the al-Jahmaliya area of Taiz.

Buildings in the al-Jahmaliya area of Taiz have been reduced to rubble, first in fighting between Houthi rebels and local militias struggling to retake the city, then in recent clashes among those local militias.

A Saudi-led coalition of Arab states, in support of the Yemeni government, imposed restrictions on the import of food, medicine and fuel.

Saudi arabia and its allies wanted to weaken the rebels but it is the civilian population who felt the consequences more strongly. The blockade, the bombs and the devaluation of the currency ravaged the economy.

At a clinic in Aslam, rooms after rooms are filled with mothers, they hold on to their malnourished children, sometimes sharing a bed with another patient. Most of the mothers are themselves malnourished.

The clinic in Aslam is overcrowded with malnourished children. Mothers and children share beds, and sometimes mattresses are added to the floor to accommodate all the patients.

The clinic is a short drive away from Al Abar village but some children, like Rageed, will never make it here, the soaring price of fuel and transportation made it too much of a burden for his family.

they come from remote regions of the Hajjah province. Bordering with Saudi Arabia, Hajjah is one of the most affected areas by malnutrition, also because of the ongoing combat. The poverty is so deep that often families have to decide which child to feed and usually girls and disabled children are left behind.

In Yemen, 85,000 children under the age of five may have died of malnutrition since 2015, according to Save the children. They often live in remote parts of the country that the conflict made challenging to reach for the Humanitarian agencies.

Some children have been treated in the clinic more than once. Their conditions improve while they are fed high-energy milk and supplements but then their health quickly deteriorates again as soon as they go back to the provinces.

The mother of Jena Mohammed Hassan, holds her 3 month old daughter on the hospital bed, in the malnutrition treatment ward of Al Thawra hospital in Sanaa. They are originally from the city of Taiz.

I spent several days photographing the work in the clinic. Every day new children arrived, but only the ones in life-threatening medical conditions could be admitted for lack of space.

They are weighed and measured and then assigned an empty bed with their mothers. They would spend a few months in the clinic before they could be discharged, but some of these children will not make it.

Fatima Ahmed stands near her daughter Nada while she undergoes the procedure to be admitted in at the clinic in Aslam. The young Nada is 5 years old and severely malnourished.

Marwah Hareb Mohammed Abdullah, 10, is measured at a clinic in Aslam, in north-west Yemen. She is malnourished but cannot be admitted because her condition is still not life threatening. Girls are often the last in the family to be fed.

Throughout Yemen, the Saudi-led coalition has carried out air raids using weapons supplied by the US and other countries. Infrastructure such as roads, factories and power stations have been targeted and as a consequence, the production and distribution of goods in a country already strongly dependent on food import became extremely expensive.

Most of the fighting is centered on the city of Hodeidah, especially after the coalition launched an offensive to retake the city from rebel control. Hodeidah’s port is the main point of entry for food imports and humanitarian aid into the Houthi-controlled northern part of the country, where most of the population of Yemen lives.

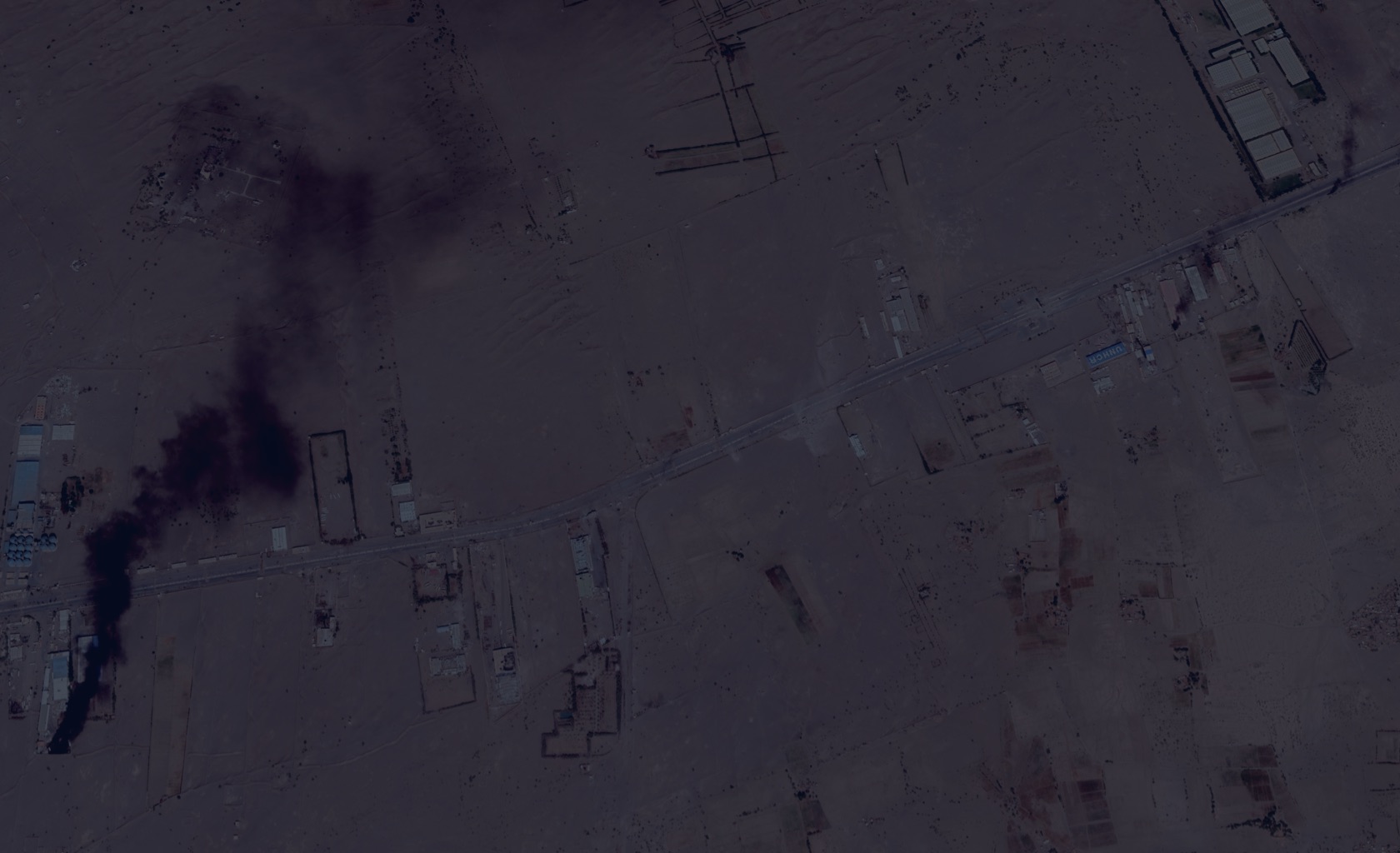

A man walks in the site of an airstrike in the Zaranek area of Hodeidah. Two people died, including a 16 year-old girl, and many were injured in the incident. The attack happened two weeks before this photo was taken.

Taking this important city on the western coast could have changed the course of the war for the coalition. Instead it amplified an already shattering humanitarian crisis and choked the import of humanitarian aid. A stock of wheat from the World Food Programme that could have fed almost four million people remained stuck for months because of the combats, and operations in the port came to an almost complete stop.

Traders buy and sell fish at the market near the port of Hodeidah. The ongoing military offensive put the fisherman in great danger. Only few of them still go out at sea now. Fishing boats have been attacked and sunk by Saudi coalition warships and helicopters and fishermen have been arrested and detained.

When I am finally allowed to visit the port in Hodeidah I find it empty. Some day laborers are sitting along the deserted docks, a single ship moored in the bay. In the distance I can see the cranes destroyed by Saudi airstrikes and the charred remains of silos and warehouses.

At the same time, thousands of miles away, in Sweden, the warring parties are sitting in front of each other to decide the fate of the city.

Houthi soldiers walk near wheat storage facilities that were damaged by Saudi airstrikes in the port of Hodeidad.

The port was at the center of the peace negotiations that finished the same day this image was taken. Negotiators agreed to transition the administration of the port to the UN and demilitarize the premises but until now these measures have not been put in place.

Dusk is falling over the quiet waters and silence descend over the place. I doubt the negotiations would bring any lasting peace; other deals have been done and broken, and the abandonment of the once thriving port did not inspire much hope in the future.

The commercial port of Hodeidah is now operating at a reduced capacity. The cranes to unload ships where damaged by airstrikes and most ships are not allowed into the port by the blockade imposed by the coalition lead by Saudi Arabia.